Where Should You Manufacture Your Products? Onshore vs. Nearshore vs. Offshore

If you don’t have your own dedicated manufacturing facility (and don’t plan to build one), you will need to find a contract manufacturer to make your products.

Clint has worked with manufacturers in the US, Mexico, Hong Kong, China, Taiwan and Japan. There are pros and cons to manufacturing in each of these places and there are many other locations around the world that offer contract manufacturing services.

Here is a summary of the pros and cons of onshore, nearshore and offshore manufacturing.

Onshore – Made in the USA

Pros

- Local manufacturing (assuming you’re based in the US)

- No international shipping to deliver goods from your manufacturer to you

- No language barrier

- The manufacturer will typically be within 1 or 2 time zones of you

- Fewer concerns about misappropriation of intellectual property

- A broad selection of high-quality contract manufacturing services is available in the US

Cons

- High cost

Summary

There are many advantages to manufacturing in the USA – and there is one dominant reason so much manufacturing has moved offshore: Cost.

If you work with a US-based contract manufacturer, you can enjoy all of the advantages listed above. But if your competitors are making similar products at an offshore contract manufacturing facility, they might be getting their products for 25% lower cost, which would put you at a huge pricing disadvantage. That, in a nutshell, is what has driven so much manufacturing offshore.

That being said, there are circumstances in which US-based manufacturing is the right decision. Here are the most common reasons to choose an onshore vs. offshore manufacturer:

- Your product requires specialized manufacturing processes that are more readily available in the US

- Concerns about misappropriation of intellectual property

- Regulatory requirements – for example, a medical device that must be manufactured in an FDA GMP compliant facility

- Patriotism – you want a “Made in the USA” label on your product and are willing to pay a premium for that

Nearshore – Made in Mexico (or Canada)

Nearshore refers to manufacturing outside the US, but in a country that has a border adjacent to the US – i.e. manufacturing in Mexico or Canada. Clint doesn’t have experience with Canadian manufacturing so the comments below refer to manufacturing in Mexico.

Pros

- Close

to US

- Lower travel costs to visit the factory and lower shipping costs

- No significant time zone differences

- Lower cost of goods than onshore (US) manufacturing

- For some products that are made in Mexico there are favorable import duties

- If your product is large or heavy, you will save on shipping costs from Mexico vs. shipping from Asia

Cons

- Smaller selection of contract manufacturers to choose from compared to US or offshore locations

- The

domestic Mexican supply chain is not as robust as the US or offshore supply

chains

- Often you will use the maquiladora program, in which you ship components and subassemblies to the manufacturer. Then the manufacturer will assemble the product and ship finished goods back to you. You will have to coordinate with your maquiladora to arrange material ordering, handling and shipping across the border.

Mexico offers lower cost manufacturing than the US and can be an attractive option. At present, the cost of labor in Mexico is roughly on par with the cost of labor in China.

Offshore – Made in China

Offshore manufacturing (from a US-centric perspective) refers to production facilities anywhere in the world outside of North America. There are contract manufacturing services on every continent except Antarctica. This analysis focuses on the pros and cons of manufacturing in China because China remains the dominant worldwide contract manufacturing location.

Pros

- Low

cost manufacturing

- Cost of labor has risen significantly in China in the past 10 years, but China still offers competitive manufacturing costs

- The largest selection of contract manufacturing facilities in the world

- The

broadest and deepest supply chain in the world

- For almost any product you could dream of manufacturing, virtually every material, component, subassembly and process can be sourced in China

- Quality

standards at Chinese manufacturers have risen significantly in the past decade

- It’s possible to get consistently good quality products from China

Cons

- Time zone difference

- Language difference

- Shipping costs and shipping times

- Higher travel costs to visit the factory

- Concerns about misappropriation of intellectual property

Comments on the cons:

Time zone difference is usually not a problem. With email and with messaging apps – and with the long working hours typical in China – you can usually get same-day responses to inquiries.

The language difference is a minor hurdle. Almost every Chinese factory has employees who speak English.

Shipping cost is usually not significant. If you ship by sea and you fill 40’ containers full of your product, shipping costs will typically add only a few percent to the landed cost of your product. You will need to factor shipping times into your order schedule. A good rule of thumb is to allow about a month for sea shipments from China (and a week for land shipments from Mexico).

Cost of travel to visit your manufacturer: Factory visits are an inevitable part of the cost of manufacturing, regardless of where the manufacturer is located. Traveling to China costs more than traveling to a site in the US or to Mexico, but the cost difference is not significant in the context of overall manufacturing costs.

There are a lot of concerns about theft of intellectual property in China. IP theft does happen, and when it occurs it makes headlines. However, there are ways to protect yourself against this. In more than 20 years of working with contract manufacturers in China, Clint has never experienced IP theft or misappropriation.

Three key ways to protect yourself against IP theft (regardless of where your manufacturer is):

- Choose your manufacturer carefully. Check references and talk to their other customers.

- Only divulge to your manufacturer the information that is necessary to build the product.

- If there is a key component in your product that contains IP that is valuable and vulnerable, consider adding that component as a final assembly step after the product arrives in the US.

China remains the preferred location for most contract manufacturing worldwide because it has the broadest and deepest supply chain in the world, and China still has competitive manufacturing costs.

Other Offshore Manufacturing Locations

There are hubs of offshore manufacturing outside of China, notably in southeast Asia and eastern Europe. If you need the absolute lowest cost of goods and if your product doesn’t require esoteric manufacturing processes, southeast Asia could be a good location for you. If you will sell a significant percentage of your product into the European Union, eastern European manufacturing might be a good option.

Bottom Line

There are many options for contract manufacturing and many variables to consider when deciding where to manufacture your product. Clint can work with you to evaluate your needs, your goals and your constraints, and help you find the right manufacturer for your product.

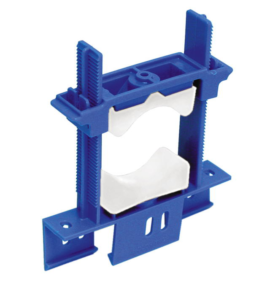

The inevitable answer is, “It depends on the complexity of the product.” The product photos shown in this case study are examples of very low-cost production ramp-ups in China. Each of these required only one or two trips to China by Clint, and the NREs to start up production (tooling, fixtures, jigs, sample runs) were only a few thousand dollars. For each of the product photos shown in this case study, the total expense to get production started was less than $10,000.

The inevitable answer is, “It depends on the complexity of the product.” The product photos shown in this case study are examples of very low-cost production ramp-ups in China. Each of these required only one or two trips to China by Clint, and the NREs to start up production (tooling, fixtures, jigs, sample runs) were only a few thousand dollars. For each of the product photos shown in this case study, the total expense to get production started was less than $10,000.