This case study illustrates one of the most valuable lessons that Clint has learned in more than 30 years of product development. This is about how small companies can compete against – and beat – much larger companies.

Two guys in a condo in La Jolla build some rockets

In the mid-80s Clint teamed up with another technology lover (Bob Hotto) to form a two-man tech company working from a condo in La Jolla. They were developing products – some on contract for other companies and some speculative product development on their own.

The General Dynamics (GD) facility that made Atlas and Titan-Centaur rockets was just a few exits down the freeway. A friend of a friend heard that GD was going to award a big engineering project – a project that entailed complete overhauls of the motors and motor control systems that are used to weld the rocket bodies. This sounded like an interesting project.

With some finagling and bit of luck, they managed to get their name added to the bid list for the project. About a month later General Dynamics invited Bob and Clint to a project preview meeting to go over the requirements of the project and the criteria for submitting proposals. The other companies who were bidding on the project were also at that meeting. This consisted of teams from every major aerospace engineering firm in America (along with Bob and Clint).

Each company had sent a team of between 6 and 10 people to the meeting. Each company had a total staff of between 5000 and 25,000 employees. All of the companies had long histories of doing contract work for GD, and it seemed like everybody in the group knew each other from past projects. This was a meeting of the professional rocket builders club. In their eyes, the rockets being assembled out on the factory floor were about as exciting as oversized tin cans. The closest Clint had been to a rocket prior to that meeting was watching launches from Cape Canaveral on TV. Comparing Clint and Bob to the other project bidders made David v. Goliath seem like a close match.

Everybody at the meeting treated Clint and Bob politely, not unlike the way in which a kindergarten teacher is polite to her not-so-bright pupils.

At the conclusion of the pre-proposal meeting everybody was given the RFP package – a stack of notebooks about three feet high. Each notebook was filled with pages of project requirements, quality standards, safety criteria, government regulations, and other insomnia-curing minutiae. Everybody had ten days to review all the documents, prepare a proposal, and then return to GD to present their proposals.

“We didn’t have a snowball’s chance in…”

Clint and Bob didn’t have a snowball’s chance in a pizza oven to win that contract. They could have offered to do the job for free and wouldn’t have been awarded the contract because the perceived risk was too high. It was impossible for them to read and digest the entire RFP package in ten days, much less write a proposal that addressed every point in the package. They had three options:

1. Go through the motions; write and submit a proposal; and get promptly dismissed.

2. Tell GD that they didn’t want to waste anybody’s time, and request to be removed from the bid list.

3. Ignore the rules, do what they do best, and try to win the project.

I’m sure you already know which option we chose. We found the five key pages buried in the RFP – the pages that listed the technical requirements for the project. We made copies of those pages then set the whole pile of notebooks in the back of a closet. Then we got to work designing and assembling a fully functional prototype of the system that we proposed to deliver to GD. We ordered components for rush delivery; we had some custom parts fabricated at a local machine shop; and we pulled a few all-nighters designing, assembling and testing.

Ten days passed very quickly and it was time to present proposals. Clint and Bob were the last of the bidders scheduled to present to GD. When we entered the meeting room, all of the GD engineers looked at their watches, wondering if they could usher us out of the room in time for lunch.

The kabuki dance

The other engineering firms had followed the rules perfectly – they knew the kabuki dance of aerospace contracts. They brought in teams of five or six senior managers. The 3-foot tall stacks of notebooks had morphed into stacks of proposals that were equally tall and that regurgitated every point in the RFP and added a few more points of their own. They presented slide shows (in the glorious days before PowerPoint) full of org charts and flow charts and man-hour allocations and project phases and schedules for the coming year. Clint and Bob didn’t have any of that.

Clint and Bob started their presentation by laying their proposal on the table – a paper binder containing five pages typed double-spaced (because if it were single-spaced, it would have only been two and a half pages). Everybody looked at their watches again and squirmed in their chairs and scowled. Then Clint and Bob said that they didn’t want to go over the proposal because that wouldn’t be a good use of everybody’s time. The scowls around the table deepened. Clint and Bob said that they would prefer to show GD what they intended to deliver. The scowls were now mixed with looks of confusion. Clint and Bob weren’t doing the kabuki dance properly!

We set a box on the table. We pulled our prototype system out of the box, plugged it into the wall, and told the GD engineers, “If we are awarded the project, this is what we will deliver, and this first unit can be installed and up and running within a week.” The prototype had a complete operator control panel and functional motors with enough torque to rotate the rocket bodies. It met or exceeded all requirements for accuracy, repeatability and reliability.

The scowls around the table turned to smiles, and then to grins that they couldn’t suppress. Every GD employee in the room took turns pushing buttons and rotating knobs on the control panel and watching the motors turn. After about 10 minutes of testing the prototype, they said, “Officially, we have to go through a series of internal approval procedures, but unofficially, you’re getting this project. Your bid has the lowest price and there is almost zero risk associated with it because a complete functional system is sitting on the table at our facility.”

That prototype was the first of six controllers to be installed at GD, and it started a three-year stream of nearly continuous projects at General Dynamics for the little two-man company.

To this day, every Atlas and Titan-Centaur rocket that is launched is made using equipment that Clint and Bob designed, assembled and installed at General Dynamics. And that 3-foot-tall stack of notebooks is probably still collecting dust in a closet in a condo in La Jolla.

Lessons

There are three important lessons in this case study:

- Don’t be intimidated by bigger, more experienced competitors. Your small size makes you more nimble and responsive.

- Recognize your strengths and have faith in them. If you think you can do it and if the big boys tell you that you can’t do it, believe in yourself and ignore the big boys.

- When something looks impossible, often it’s because the “impossible” things are blocking your view. Shove the pile of impossible things into a dark corner and clear your desk. Then try to understand the real goals and figure out how you can achieve them.

If you could benefit from some “outside the box” thinking to help you compete – against the big boys or against your peers – please call or email Clint to see if he can help you.

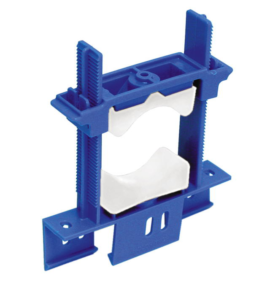

The inevitable answer is, “It depends on the complexity of the product.” The product photos shown in this case study are examples of very low-cost production ramp-ups in China. Each of these required only one or two trips to China by Clint, and the NREs to start up production (tooling, fixtures, jigs, sample runs) were only a few thousand dollars. For each of the product photos shown in this case study, the total expense to get production started was less than $10,000.

The inevitable answer is, “It depends on the complexity of the product.” The product photos shown in this case study are examples of very low-cost production ramp-ups in China. Each of these required only one or two trips to China by Clint, and the NREs to start up production (tooling, fixtures, jigs, sample runs) were only a few thousand dollars. For each of the product photos shown in this case study, the total expense to get production started was less than $10,000.